“The crowds of men who merely spoke the Greek and Latin tongues in the Middle Ages were not entitled by the accident of birth to read the works of genius written in those languages; for these were not written in that Greek or Latin which they knew, but in the select language of literature. They had not learned the nobler dialects of Greece and Rome, but the very materials on which they were written were waste paper to them, and they prized instead a cheap contemporary literature.” — Henry David Thoreau, “Reading,” Walden

Thoreau is alluding to an old idea which was more common in his time than it is in ours: the idea that the best ideas are the most “noble” and can only be expressed in elevated, refined language, even to the point of being beyond translation.

Today we’re less inclined to look to ancient poets for wisdom, and elevated language often sounds pretentious to the modern ear.

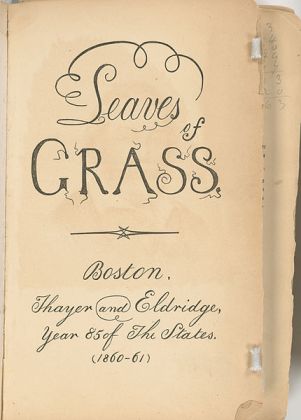

If he had lived longer, what would Henry have made of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain’s masterpiece? Would he, like many contemporary critics, have considered it a low, vulgar book, or would he have recognized it as a work of literature? For what it’s worth, he was enthusiastic about Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, second edition. Though he was uncomfortable with its overt sexuality, he didn’t dismiss the book as vulgar trash as many of his contemporaries did. His embrace of Whitman’s work shows that Thoreau wasn’t stuck in the past but could appreciate new styles and vocabularies of expression.

(About “A Year in Walden”)